Damping factor

- The term damping factor can also refer to the damping ratio in any damped oscillatory system or in numerical algorithms.

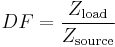

In audio system terminology, the damping factor gives the ratio of the rated impedance of the loudspeaker to the source impedance. Only the resistive part of the loudspeaker impedance is used. The amplifier output impedance is also assumed to be totally resistive. The source impedance (that seen by the loudspeaker) includes the connecting cable impedance. The load impedance  (input impedance) and the source impedance

(input impedance) and the source impedance  (output impedance) are shown in the diagram.

(output impedance) are shown in the diagram.

The damping factor  is:

is:

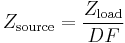

Solving for  :

:

Contents |

Explanation

In loudspeaker systems, the value of the damping factor between a particular loudspeaker and a particular amplifier describes the ability of the amplifier to control undesirable movement of the speaker cone near the resonant frequency of the speaker system. It is usually used in the context of low-frequency driver behavior, and especially so in the case of electrodynamic drivers, which use a magnetic motor to generate the forces which move the diaphragm.

Speaker diaphragms have mass, and their surrounds have stiffness. Together, these form a resonant system, and the mechanical cone resonance may be excited by electrical signals (e.g., pulses) at audio frequencies. But a driver with a voice coil is also a current generator, since it has a coil attached to the cone and suspension, and that coil is immersed in a magnetic field. For every motion the coil makes, it will generate a current that will be seen by any electrically attached equipment, such as an amplifier. In fact, the amp's output circuitry will be the main electrical load on the "voice coil current generator". If that load has low resistance, the current will be larger and the voice coil will be more strongly forced to decelerate. A high damping factor (which requires low output impedance at the amplifier output) very rapidly damps unwanted cone movements induced by the mechanical resonance of the speaker, acting as the equivalent of a "brake" on the voice coil motion (just as a short circuit across the terminals of a rotary electrical generator will make it very hard to turn). It is generally (though not universally) thought that tighter control of voice coil motion is desirable, as it is believed to contribute to better-quality sound.

A high damping factor indicates that an amplifier will have greater control over the movement of the speaker cone, particularly in the bass region near the resonant frequency of the driver's mechanical resonance. However, the damping factor at any particular frequency will vary, since driver voice coils are complex impedances whose values vary with frequency. In addition, the electrical characteristics of every voice coil will change with temperature; high power levels will increase coil temperature, and thus resistance. And finally, passive crossovers (made of relatively large inductors, capacitors, and resistors) are between the amplifier and speaker drivers and also affect the damping factor, again in a way that varies with frequency.

For audio power amplifiers, this source impedance  (also: output impedance) is generally smaller than 0.1 ohm (Ω), and from the point of view of the driver voice coil, is a near short-circuit.

(also: output impedance) is generally smaller than 0.1 ohm (Ω), and from the point of view of the driver voice coil, is a near short-circuit.

The loudspeaker's load impedance (input impedance) of  is usually around 4 to 8Ω, although other impedance speakers are available, sometimes as low as 1Ω.

is usually around 4 to 8Ω, although other impedance speakers are available, sometimes as low as 1Ω.

The damping circuit

The voltage generated by the moving voice coil forces current through three resistances:

- the resistance of the voice coil itself;

- the resistance of the interconnecting cable; and

- the output resistance of the amplifier.

Effect of voice coil resistance

This is the major factor in limiting the amount of damping that can be achieved electrically, because its value is larger (say between 4 and 8 Ω, typically) than any other resistance in the output circuitry of an amplifier that does not use an output transformer (nearly every solid-state amplifier on the mass market).

A loud speaker's flyback current is not dissipated only through the amplifier output circuit, but also through the internal resistance in the speaker itself.

Even if the resistance of the speaker cable and of the amplifier is 0 Ω, the speaker still faces the resistance of its own voice coil wire.

Therefore, damping factor values above 50 or so are not meaningfully different from 50. For higher values of speaker damping than about 50, actual speaker damping no longer increases in any way that can be confirmed by a double-blind A/B listening test, or measured.

Effect of cable resistance

The damping factor is affected to some extent by the resistance of the speaker cables. The higher the resistance of the speaker cables, the lower the damping factor. When the effect is small, it is called voltage bridging.  >>

>>  .

.

Amplifier output impedance

Modern solid state amplifiers, which use relatively high levels of negative feedback to control distortion, have extremely low output impedances—one of the many consequences of using feedback—and small changes in an already low value change overall damping factor by only a small, and therefore negligible, amount.

Thus, high damping factor values do not, by themselves, say very much about the quality of a system; most modern amplifiers have them, but vary in quality nonetheless. Given the controversy that has long surrounded the use of feedback, some extend their distaste for negative feedback amplifier designs (and so a high damping factor) as a mark of poor quality. For them, such high values imply a high level of NFB in the amplifier.

Tube amplifiers typically have much lower feedback ratios, and in any case almost always have output transformers that limit how low the output impedance can be. Their lower damping factors are one of the reasons many audiophiles prefer tube amplifiers. Taken even further, some tube amplifiers are designed to have no negative feedback at all.

In practice

Over a range from less than 1 to up to around 50, damping factor describes the ability to which the amplifier helps to control the oscillation of the speaker, expressing the degree to which the amplifier does not exert a resistance against the current generated by the speaker. A damping factor of 50 is high, indicating that the output impedance of the amplifier is negligible compared to the internal resistance of the speaker and the speaker cabling.

Higher electrical damping of the loudspeaker is not necessarily better. Some loudspeakers sound better with lower electrical damping. A lower damping factor helps to greatly enhance the bass response of the loudspeaker, which is useful if only a single amplifier is used for the entire audio range. Therefore, some amplifiers, in particular vintage amplifiers from the 1950's, 60's and 70's, feature controls for varying the damping factor.

One example of a vintage amplifier with a damping control is the Accuphase E-202, which has a three-position switch described by the following excerpt from its owner's manual:[1]

- "Speaker Damping Control enhances characteristic tonal qualities of speakers. The damping factor of solid state amplifiers is generally very large and ideal for damping the speakers. However, some speakers require an amplifier with a low damping factor to reproduce rich, full-bodied sound. The E-202 has a Speaker Damping Control which permits choice of three damping factors and induces maximum potential performance from any speaker. Damping factor with an 8 ohm load becomes more than 50 when this control is set to NORMAL. Likewise, it is 5 at MEDIUM position, and 1 at SOFT position. It enables choosing the speaker sound that one prefers."

By contrast, in modern high fidelity amplification, the trend is to separate the bass signal and amplify it with a dedicated amplifier. Often, amplifiers for bass are integrated with the speaker cabinet, a configuration known as the powered subwoofer. In a topology that includes a dedicated amplifier for bass, the damping factor of the main amplifier is not relevant, and that of the bass amplifier is also irrelevant if that amplifier is integrated with the speaker and cabinet as a unit, since all those components are designed together and optimized for the reproduction of bass.

Damping is also a concern in guitar amplifiers, an application in which low damping is better. Numerous guitar amplifiers have damping controls, and the trend to include this feature has been increasing since the 1990's. For instance the Marshall Valvestate 8008 rack-mounted stereo amplifier[2] has a switch between "linear" and "Valvestate" mode:

- "Linear/Vstate selector. Slide to select linear or Valvestate performance. The Valvestate mode gives extra warm harmonics plus the richness of tone, which is unique to the Valvestate power stage. Linear mode produces a highly defined hi-fi tone that gives a totally different character to the sound and suits certain modern "metal" styles, or PA applications."

This is actually a damping control based on negative current feedback, which is evident from the schematic,[3] where the same switch is labeled as "Output Power Mode: Current/Voltage". The "Valvestate" mode introduces negative current feedback which raises the output impedance, lowers the damping factor, and alters the frequency response, similarly to what occurs in a tube amplifier. (Contrary to the claim in the handbook, this circuit topology has has appeared in numerous solid-state guitar amplifiers since the 1970's.)

See also

- Impedance

- Input impedance

- Output impedance

- RLC circuit

- Voltage divider

- Audio system measurements

- Damping

Footnotes

- ^ "Accuphase E-202 Integrated Stereo Amplifier". http://www.accuphase.com/cat/e-202en.pdf. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- ^ "Marshall Valvestate Power Amplifiers Handbook". http://www.marshallamps.com/downloads/files/8004_8008%20hbk.pdf. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- ^ "Marshall 8008 Valvestate Schematic". http://www.drtube.com/schematics/marshall/8008.pdf. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

References

- Julian L Bernstein, Audio Systems p364, pub John Wiley 1966

External links

- Radio Electronics - December 1954 and January 1955, D. J. Tomcik, Missing Link in Speaker Operation

- Marantz's Legendary Audio Classics. Ben Blish, Damping Factor

- Audioholics. AV University. Amplifier Technology. Dick Pierce, Damping factor: Effects on System Response

- ProSoundWeb. Studyhall. Chuck McGregor, What is Loudspeaker Damping?